The Media, the 2019 Election and The Aftermath

Edited by Granville Williams

Published by Campaign For Press And Broadcasting Freedom (North)

£9.99

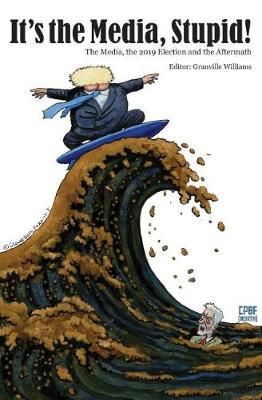

‘It’s the Media, Stupid’ – The Media, the 2019 Election and the Aftermath’ sounds like an accusation, it is in fact the title of a book skillfully edited by Granville Williams of the Campaign for Press and Broadcasting Freedom [North], that looks into what’s happened to the media since the election and the run up to it.

Throughout the 2019 election CPBF produced Election Watch, some of the comments included in the book come from those and from a conference held in February. It includes chapters from journalists and luminaries such as the much respected former BBC Industrial and Political correspondent Nick Jones, and Tony Burke, former Deputy General Secretary of the GPMU and now Assistant General Secretary of Unite and former print worker using their experience to try and analyse what happened.

I have worked on both sides covering elections as a reporter for national/local papers and for national radio, and previously as a press officer for Labour during the 1970 election; later quietly working for Labour behind the scenes during campaigns I was reporting. I have also worked as a TUC press officer and represented journalists as a National Organiser for the NUJ so my feelings about the media have ranged from desperation to frustration. Many of those feelings are mirrored in the book, particularly those in relation to the BBC, formally seen as an independent defender of the truth but now looked on as having compromised its reportage in favour of the establishment.

The book also looks at how the Tory Government treats those critical of them since the election. The failure by the media to hold the Government to account for the way it has handled the pandemic is already coming under scrutiny.

In his foreword Professor James Curran of Goldsmith University, himself a writer of previous studies on press coverage of politics refers to the British public having lost their trust in the media: ‘Britain’s Trust in the British press,’ he writes ‘ is now even lower than that of Serbians in their press, while trust in British broadcasting has fallen before the EU average’. Certainly the Millie Dowling coverage which saw the closure of the News of The World did much to expose how the media, in particular red tops had given up any vestige of decency in attempts to get a quick headliner. Something that those of us who had ever dealt with Murdoch had known, but the public now had demonstrated to them.

The editor of the Soviet news outlet Pravda once said to me: ‘the problem is that you think you have press freedom, you don’t, your papers are owned by a few with their own interests; we know we haven’t, so we aren’t tricked’. He was right. The Mail’s publication of the Zinoviev letter in 1924 a few weeks before the General Election which produced the collapse of the Liberal Party and landslide victory of the Tories led to Labour taking steps to distance itself from left socialist leaning policies which could be likened to Communist tendencies. The letter was of course a forgery, but the public believed it. It was an early indication as to how the right wing press, who would go on to support Mosley and the blackshirts, would treat Labour. And to what depths it would plunge and still will do as has been shown more recently.

Certainly coverage of the Labour Party, and in particular on Corbyn since the 2017 election was even more viscious than those previously conducted. Leaders of the Labour Party have always come under attack from the press. Neil Kinnock was portrayed as a joke Welshman in attacks that at times seemed racist, the attacks on Ed Miliband made by the Mail, were. Harold Wilson was described as a Russian spy and Michael Foot as a tired out old eccentric. Clement Attlee, after whom the English section of the International Brigade was named was seen as fair game before the war, was accused in the 1945 General Election by Winston Churchill as having plans to set up a gestapo. Fortunately the British public knew Attlee and saw through the attempts at vilification.

The difference between Corbyn and his predecessors was that the general public didn’t know much about him, other than what they were told about him by the media. One thing was certain and that was that none of the proprietors were going to accept even the remotest possibility of someone like Corbyn becoming Prime Minister. No other leader received the level of hits against them that Corbyn received, some 5,000. It was as Nicholas Jones rightly complains a ‘hatchet job that was the vilest I have witnessed in 50 years of political reporting’.

‘Any semblance of trustworthiness he might have accrued as leader of the opposition was torpedoed in a sea of slurs and smears. A masterclass in character assassination was delivered with shameless superiority.’

As Jones writes: ‘Rarely have editors and columnists of Conservative supporting newspapers been so calculated or so co-ordinated in demolishing the credibility of a British politician.’

We have to deal with the Media that we have got. It’s one that is being reduced as papers are cut back or closed, or go on line. Particularly vulnerable have been local papers bought up by large paper groups, closed down as circulations fell. Independent voices covering local politics are being squeezed out. Unions are no longer in a position to shut down a paper for a story they disagree with. In the 70s as television and local radio took on the press; local and national, papers and groups passed into new ownerships. Ownership is now becoming even more compressed. In 2019, 83% of the market was owned by three groups, giving them more power and influence than they have had before making them even more difficult to make answerable for what they do. Nationals in particular have swung even harder against Labour and the unions. Thatcher, aided by Murdoch and the others right wing owners changed the climate in this country in the 1980s and 90s dumbing down information to that of the celebrity and ‘me’ generation. The Campaign for Press Freedom was set up in 1979 supported by the NUJ and Print unions. It later widened its scope in 1982 to take in broadcasting, a portent of what was to happen as commercial TV quality was sacrificed to raise money to bid for new licenses. The NUJ who represented many of the journalists on the papers which many now themselves no longer respected, realized that there was a professional need to redress the balance against the lies, distortions and vindictive campaigns. Granville Williams, this books editor was and remains a prominent advocate leading CBPF [North].

Tony Burke, himself a longtime supporter of the campaign and Louisa Bull, a former NATSOPA/SOGAT rep now UNITE National Officer for the Graphical, Paper, Media and IT sector’s chapter take a pragmatic attitude towards detailing the history of papers and the growth of social media, an area which also needs some form of regulation to give standards within the latter, they call for media unions, progressive academics and activists to ‘clarify and campaign for effective, independent, transparent regulation.’

A call that is prescient as the future of newspapers as a provider of news is doubtful. The report just published by Labour Together on the General election says that the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at Oxford University found that in 2018 on line media, including social ones have become the more important source of news than print for every age group, though social media considered on its own is still less important for those aged 45+.

Union activity in the media is also highlighted by tony Burke and Louisa Bull showing how unions often estranged in the past came together in the early 1990s to form Press For Union Rights set up to the fight deregulation.

Sadly attempts to amalgamate the NUJ and the print union the NGA in the 1980s failed but realisation that a new harder political climate, dealing with media groups controlling all aspects of publishing and broadcast media which would destroy union rights led to others coming together, as has been reflected in UNITE membership.

Interestingly it was his debates on TV which had helped Corbyn to break through barriers to recruit voters to his side when he stood in the leadership election of 2015. But in many ways it was his performances on TV during the 2019 campaign with the addition of highly biased coverage that had built up over the last few years that were used against him. Three of the chapters in the book look at the BBC’s performance. Nicholas Jones portrays how broadcasters instead of leading and taking their own views found themselves increasingly led and following up stances and stories published in red tops. But it was evident from 2017 that the BBC had metamorphized into becoming a commentator and critic of Corbyn. It’s pro brexit coverage in the referendum certainly showed it was willing to take a political line that it had not done in the past. Burke and Bull also refer to how even the slanted newspaper front pages shown on screens for comments from reviewers or on news programmes all subtly added to a negative portrayal of Labour and Corbyn.

We read what paper owners want us to, we do expect an independent, impartial line from our own public broadcasting service. But whilst the BBC may sometimes follow the newspaper lines, that hasn’t stopped it from coming under fire from newspapers. The future of the BBC and its license and independence is now open to question as a hostile Government which shows its contempt for the public looks at what is to become of it. This book though critical of its failures to show impartiality argues that that the principle of Public Service Broadcasting must be maintained. It calls for more public participation in making it answerable, and that there should be competition for quality. Something that is also called for in the commercial television and radio companies.

This book includes illustrations of the front pages used to attack Labour and Corbyn; it also includes chapters that cover antisemitism, the youth vote as well as other aspects of press coverage. It doesn’t shy away from being critical of Labour’s own election campaign nor of the way that Corbyn’s team dealt with the attacks, sometimes taking a defensive role that did far from allaying the disquiet that grew up around him because of past connections and behaviour. This country is in the midst of the pandemic which is expected to lead to a recession as bad as that of the 1930s, possibly worse, as we look like leaving the EU without any trade deal. Unemployment is now the highest we have experienced. It’s essential that we have a media, social or otherwise which asks the right questions, fights to make sure that one of the worst Governments on record is called to account. Never more has this country needed a strong media unafraid of taking on the establishment. It’s The Media, Stupid, takes a hard look at what has happened and opens up discussion on what can be done to enable this.

As Granville William writes this book is part of a CBPF (North) initiative ‘to arouse public awareness of the vital importance of diverse, independent media’. This book certainly does this.